George McGee, ill a photographer’s studio in

Belgium as they headed towards Germany at the end

of World War 1.

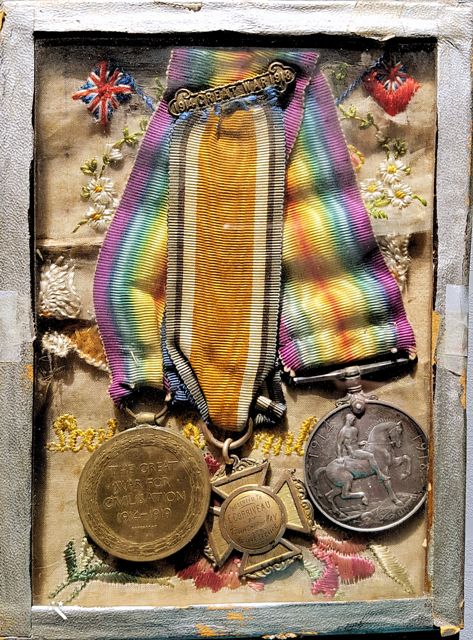

A SOLDIER REMEMBERS WORLD WAR I

Private Edward Napoleon Corriveau, 22, of the French Settlement, #3131814, 4th Reserve BN C.E.F. of Company B, enlisted on February 25, 1918. He trained as a machine gunner but instead acted as an interpreter throughout the war. This is his story, recorded by his granddaughter, Elaine Coxon.

“We first went to London (Ontario) and were then sent to St. Thomas to train. We lived in a broom fac tory and the first night there, I didn’t sleep at all. They were shunting the trains, fixing them up for the next morning and that old engine would be going all night. It made a terrible noise but we all got used to it after that. During the day, we would be on the parade grounds, practising all the time. We walked and we learned how to keep in step and we exercised. After six weeks there, we returned to London at Carling Heights for a couple of weeks, where we were trained on our weapons. From there, we took a train to Montreal … We boarded a boat called the Thomwa: it was an Indian name. We sailed up the St. Lawrence towards Halifax.

About 14 or 16 miles from Halifax, we hit what they called a ‘black rock’ and our ship began to take on water around 7 a.m. We shot off our cannons to signal for help but had to stop because with each shot, we could hear the boat grinding on the rock. We did make radio contact with a French boat. I was the one who told them, in French, what had happened. They radioed back that we could expect help from an American ship, the Aztec. The Aztec arrived at 2 p.m. and by now the water was almost up to our sleeping bunks. We were loaded onto lifeboats – 22 men per boat. We had to climb down rope ladders. It was awfully rough and when the lifeboats would come up on a swell, someone hollered “go” and you had to let go of the rope and jump. If you didn’t let go when you were supposed to, someone else would step on your fingers … To board the Aztec, we once again had to climb a rope ladder and this time as we neared the top of the ladder, they would grab a hold of us and pitch us onto the boat like fat pigs. Because we had to load and unload so fast, that was about the only way. I admire the American soldiers -how good they were on the rowboats – really good sailors.

It had rained all day. All 250 of us were wet, cold and hungry. We were taken to a hospital nearby and fed macaroni and cheese. When that ran out, they served us boiled potatoes and those were pretty good … We then moved to a camp in Halifax where we were given more clothes, as everything was lost with the ship. We stayed here for ten days, waiting on a new ship that would take us overseas. They sent us the City of Vienna, an old fishing boat. When we first boarded her it stank so much of dead fish, that we turned around and got off. She was then washed down again before we set off for England.

Eleven and one half days on the Atlantic brought us to Tilbury, England. When we neared the harbour, our ship tilted on its side. The water was gone and you could see the weeds on the bottom of the ocean. I didn’t know what it was until I started talking with someone on deck and they explained what tides were. We waited until the tide came in and all at once our boat straightened up. From here we walked about 15 miles to Whitley Camp where we were quarantined and trained for another three months. Then we crossed the English Channel to France.

We then set out to reinforce the 1st Canadian Battalion. There were only 12 to 18 men left with their captain. The whole battalion had been wiped out – either wounded or killed in their last battle. Most of our 250 men stayed here. I think a few may have gone on to join the Second Battalion. We were now just a short piece from Ardennes (or possibly Varennes) in France, about four or five miles from the battle front.

On the evening of November 10, 1918, we were given orders to have everything ready to move out the next morning. We were going to the front. We all felt more like going ahead rather than staying in one spot. It’s a funny thing, but we were no more scared than anything. Most of us were ready to go, because a soldier doesn’t like to stay in one place all the time – they feel like they have to move on. The next morning, I and a few others were up kind of early and walking around. We came to the bulletin board and read a notice that the war was over. It was welcome news, I tell you! The war was over and we weren’t going to the front. Around 10:40 or 10:45 that same morning, a captain took some of his men over the top. Something like five or six of them were killed. I think the captain knew that the war had ended. They should not have gone. They died the very day that Armistice was signed. After the signing, we did go a little crazy and started to celebrate. Men were firing their machine guns and it sounded like firecrackers going off at night.

A day or two after Armistice Day, we were assigned to escort the German soldiers back to their country. We walked through France, across Belgium and into Germany, as far as the Rhine River. We probably walked 30 to 35 miles each day. We usually stayed a half day’s march behind the Germans. They were all worn out and we were fresh, you see. They had to bring their horses, mules and belongings with them. Many of their horses died on them. It was very common to find dead horses on the roadside – three or four teams sometimes – all in a row. I remember one day we all sat on dead horses to have our dinner. It was better than the mud which was six inches deep. There were seven or eight of us sitting on one horse but at least it was dry.

I went ahead with the billeting party. I acted as the French interpreter in France and Belgium. It was our job to find places for the battalion to sleep at night. In some places we found rooms for them in people’s homes. We would mark the number of men that could stay in the house with chalk. We would go into the place, round up the furniture into one corner and we would eat, and sleep on the floor. One blanket each and that was it.

In one place, we slept in barracks, on small straw mattresses. As it turns out, they were full of fleas. That first night, I was smoking a cigarette and looked down my shirt because it was itchy as hell. Sure enough when I went to touch my chest, something jumped and bit me further on. The next morning we all showered, put on clean clothes and burned all of the straw and everything on it. We just used our blankets for a mattress. I still have a strip across my chest where you can tell it’s been chewed up.

We arrived in Germany on December 4, 1918 and stayed over Christmas and New Year’s until the 15th of January, 1919. It was the dead of winter and we slept in a bar room on cement floors. We had one blanket and an overcoat. We would put one layer of the blanket on the floor and lay the other half over us. We would cover ourselves with our overcoats and used our tunics for pillows. We were just about frozen when we went to sleep but we’d always wake up just as warm as toast.

I never saw battle, so I never shot anyone … all I ever killed over there was a pigeon and I caught hell for that. I brought it back to the family where I was staying and as it turned out, it was their daughter’s pet.

We didn’t do much in Germany – just enjoyed ourselves a bit, walked around and talked to some of the Germans. We weren’t too sure of ourselves with the Germans at the start, but they were all right.

A soldier ‘s pay was $1 a day with 10 cents field allowance for buying things such as shoe polish and shaving cream. We were paid in the currency of the country we were in. I remember when we went for a haircut and a shave. We tossed to see who would sit in the chair first. You see, if the barber made a bad move, we were ready to fix him! Anyway, I had to sit on the chair first and by golly, if the barber, himself wasn’t shaking! … I got my shave and haircut for about five cents and I gave him a piece of paper money that I had. I didn’t know what I was going to get back in change but it turned out to be a whole handful of the stuff!

We walked through all of the battlefields on our way to Germany. There were a lot of dead soldiers. At one place there was a kind of little lake with four or five German soldiers floating in it. Often times you would see just a hand or a boot sticking out of the ground. We would bury some or at least cover them over when we went by…Stuff like that really never bothered me – when you’re in the army – you gotta be tough. I remember, one old lady in Germany who didn’t want us to put men in her house. I went over to my captain and asked him what I should do. She just sat on her step and refused. He looked at me and said, ‘Shoot her!’ Now, I wasn’t about to do that! He didn’t mean it- at least not as an order – but people who have been in the war for four or five years do get hardened.

I really don’t know what my favourite part was – nothing was too favourite. There was discipline in the war – that’s what you needed. You had to have discipline. To say that I was crazy about the army, I wasn’t. I would have better cooks for one thing!”

Reprinted from the Hay Township Highlights book with permission from Elaine Coxon.