The first application to the Canadian Government for a Charter to construct a canal from Lake Huron to Lake Erie was made by Narcisse Cantin in 1898. The corporation was to be called the Huron & Erie Canal Company and proposed to build a canal running from St. Joseph to Lake Erie ending at a point between Port Talbot and Port Stanley.

Cantin’s vision included a canal paralleling and located west of today’s Welland Canal, entering Lake Ontario between Hamilton and Port Dalhousie. From that point, shipping would continue east on Lake Ontario to Prescott, where another canal would link Prescott to Ottawa. From Ottawa, via the Ottawa River, shipping would move to the St. Lawrence and Montreal Harbour by way of Riviere de Praires.

Cantin believed hydro electric power developments would advance along with the canal projects and create enough electricity to power southern Ontario’s railroad system.

Rationale for the canal

The feasibility for Cantin’s project was based on:

- Travel distance,

- Freight handling, and

- Quantity of shipping.

Inbound or outbound freight travelling the Great Lakes passed through an “unnecessary” 241km (150 miles) through the St. Clair River and Detroit River to either Lake Ontario or Lake Huron, which translated into 483km (300 miles) for round trips. Differences in water depth necessitated additional handling of freight, as it was unpacked and repacked between large great-lake ships to smaller canal boats and barges.

According to Cantin, “Lake Huron is the hub lake of the North American Continent. More freight is borne on its waters than passes through the Suez Canal.”

“I saw that a canal between lakes Huron and Erie would be an economical proposition and would bring entirely into Canadian Territory the pivotal point of the greatest transportation and industrial activity in the world.”

Canadian federal engineers were satisfied with Cantin’s canal proposal. Unfortunately, Cantin faced political, financial and competitive challenges. He failed to receive the Charter in 1898, 1902, 1903, 1904 and 1907, but continued to petition for incorporation with rights to construct canals for the next decade.

1902 – Bill 80 and the Huron & Erie Canal Company

In 1902, Bill 80 was introduced to the House of Commons. The bill’s objective was to incorporate the Huron & Erie Canal Company. It received and passed first and second readings in the House of Commons and Senate.

The Huron & Erie Canal Company’s charter would grant the power to build a canal from Lake Huron to Lake Erie, a distance of about 80km (50 miles). Cost estimates were between $25 million and $35 million. Bill 80 was withdrawn owing, as Cantin remarked, “to the Canadian Parliament’s lack of interest.”

1903 – Bill 151 and the St. Joseph Transportation Company

On May 5, 1903, Cantin’s second application to incorporate a canal-building company, Bill 151, received its first reading in the House of Commons. This time the proposed corporation’s name was the St. Joseph Transportation Company.

The Buffalo Enquirer interviewed Cantin and quoted him as saying: “It is our purpose to construct the proposed canal between St. Joseph and (a point)…three miles (5km) west of Port Stanley. The topographical condition of the country is such that but one lock will be necessary in the entire distance. Vessels will be moved by electric cables, the nine foot (2.7m) drop which makes a lock necessary being utilized to furnish power to run the motors.”

Unlike many charter requests of the time, Cantin’s application did not ask for any government subsidies. The corporation’s financing would come from private investors. Directors of the proposed St. Joseph Transportation Company were:

- Joseph T. R. Laurandeau of Montreal,

- George l’Magnan of Toronto,

- W.W. Beverley of New York,

- Frederic Belanger of New York,

- Louis G. Routhier of Ottawa,

- Taissaint G. Coursolles of Ottawa,

- James White of Ottawa, and

- Oliver Cabana Jr. of Buffalo.

Capitalization would be through the sale of stock in the amount of $10 million divided into shares of $100 or 100,000 shares.

Bill 151 received its second reading in the House of Commons and first and second readings in the Senate, but failed on its final reading. Cantin exerted no further pressure on the Government to push the Bill along and get it passed, “in order to meet the request and wishes of certain politicians with whose projects it then conflicted”.

On August 3, 1903, Cantin received a request from Greenshields, Greenshields and Heneker, Montreal Lawyers, requesting that Bill 151 “not be proceeded with further…to avoid clashing with Colonel Tisdale’s Bill”. Tisdale’s Bill was to empower his company to connect Lake St. Clair with Lake Erie by a canal. It is difficult to say why Cantin was asked to withdraw his Bill and not Tisdale and why Cantin agreed.

1904 to 1911 – Support and interest from the influential and powerful

In 1904, Cantin again sought incorporation of the St. Joseph Transportation Company. Like the previous year, both the House of Commons and Senate gave the bill preliminary readings, after which the bill failed to pass. This time, Cantin appealed personally to Prime Minister Laurier, who advised him nothing could be done “on such a vast scheme until another government proposal”, the arrangements for the completion of the partly constructed Inter-Colonial Railway system, had been achieved.

Although there was no documented government opposition to Cantin’s canal proposal, it could be speculated there was concern Cantin’s project would draw investment capital away from other government-favoured developments.

As well, a Lake Huron to Lake Erie canal may have been considered unnecessary since there already was a connection between the lakes through the Detroit River, regardless of navigational hazards, growing congestion, greater distance or increased freight handling.

On September 24, 1906, The London Free Press published an editorial in favour of Cantin’s canal project, saying, “there are no engineering difficulties that cannot be overcome”. The editorial mentioned the difficulty of financing, but one likely would be overcome given the project’s merit. The newspaper agreed with Cantin’s arguments that a Huron to Erie canal would shorten the route from Duluth to Pittsburg by twenty hours and that the congestion, shoals and other hazards of the Detroit River would be avoided. “The expense of keeping the river channel open and secure is so great that it is not surprising to hear of a proposed survey for a canal across Ontario”.

The Toronto Star interviewed Cantin in May 1906. In the article “N.M. Cantin Plans Canal“, it states Cantin produced a “document signed by a number of capitalists reciting that, whereas Mr. Cantin is endeavouring to secure a charter for this canal project, they subscribe to it etc etc. The names Mr. Cantin does not give for publication, but they were shown to the Interviewer and include prominent men in Ottawa, Montreal, Buffalo and New York”.

In January 1907, Cantin once again applied for Charter to incorporate the St. Joseph Transportation Company. The Bill received the first and second readings in the Senate, but failed on final reading. This time the provisional directors were all from Ottawa:

- Joseph Ulric Vincent — Ottawa lawyer, who established the law firm of Vincent Dagenais Gibson one year after the establishment of the Canadian Bar Association in 1896; ran for political office in County Russell,

- Joseph M. Lavoie,

- Rodolphe Chevrier — Ottawa lawyer, barrister, judge and member of parliament,

- Louis C. Prevost,

- William B. Renaud — Ottawa lumberman’s agent,

- Elizee G. Laverdure,

- Auguste Lemieux — Ottawa lawyer,

- Alphonse A. Taillon — Ottawa banker,

- Tertullien Lemay — Retailer, and

- Jean-Baptiste Couillard.

Again, the company would be financed through $100 shares to the amount of $50 million.

Cantin continued to seek interest and investors for the canal project, among them:

- Donat Raymond — who later became a Canadian Senator, founder of the National Hockey League and a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, evidently was “impressed with the project and the people connected therewith and became personally, financially interested and remained so until 1927 and invested several thousand dollars”

- Charles Schwab —Bethlehem Steel, discussed the project with Cantin in Montreal, September 1908 and “advocated the idea of the project, but declared the time premature for the general public to accept its feasibility and economic advisability. He advised the public be educated by well directed propaganda”

- Ralph W. Levy — “The Cotton King of New Orleans” — wrote to Cantin September 24, 1908, about an upcoming meeting with Cantin in Montreal, “were it not for the absolute confidence we place in you, we certainly would not attempt such a trip”

- Woods — Erie Railroad

- Charles Reed of New York

- J.B. Fosburgh — James Stewart and Company, New York contractors – wrote Cantin in October of 1908 saying, “your courage and perseverance in undertaking the matter certainly deserve much”

- James A. Farrell — President of the United States Steel Corporation

- Hormisdals Laporte — Mayor of Montreal (1908)

At the time, Cantin had the interest of major industrial and financial figures, but had not been able to obtain the Charter.

1911 – Post WW1: The Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company

By 1911, Cantin had moved to Toronto and the Canada Gazette published notice of application for incorporation of The Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company. Incorporated May 30, 1914, the Company had the power to obtain “all the data, plans, maps, and other properties heretofore obtained by the promoter, who since 1896 had accumulated very valuable data and properties”, but it had not obtained the power to construct canals.

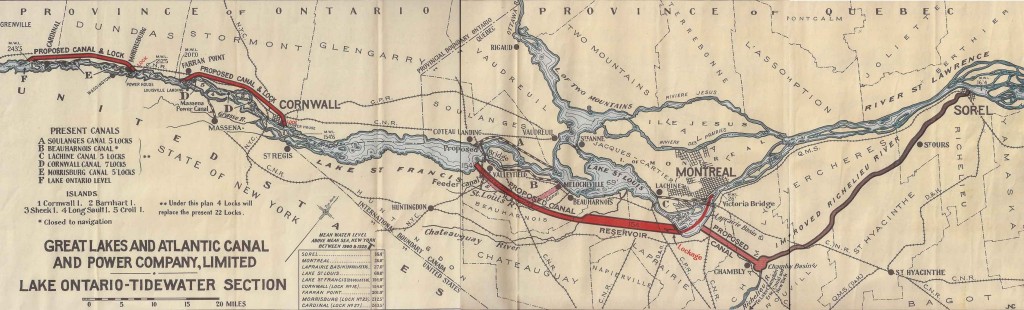

At this point, Cantin expanded upon his original canal idea to one that proposed a series of canals to the make the entire St. Lawrence River system navigable. This series of canals would be 10 metres deep (33 feet) and 120 metres (394 feet) wide at a cost of no more than $500 million. The canal system would start with Cantin’s original idea of a one-lock canal from St. Joseph to Lake Erie, then a six-lock canal from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario west of the old Welland Canal. From the eastern end of Lake Ontario, the system would include a canal from Prescott to Ottawa and then down the Ottawa River to Montreal.

A few weeks later, in August 1914, World War I began and Canada’s energies were devoted to the war effort. Cantin and the Company were not able to pursue the project for the next four years.

Post-War Cantin remained optimistic and began a communications campaign to raise the public’s awareness of the Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company Limited and the feasibility of the canal project. He distributed various print materials to major Canadian and American newspapers, cabinet Ministers, Members of Parliament, Senators, financiers, and anyone else who might be helpful. In one of his booklets states: “now that victory is ours, and peace is to reign once more and as our country has been stirred up to economic turmoil during the last four years of war, undertakings which seemed as great tasks and almost impossible before the war, are now looked upon by our returned soldiers as easy to accomplish”.

Public & Political Awareness Raised

Newspapers in Toronto, London, Montreal, Chicago and Detroit commented editorially on the need for the deep water channels being proposed. In 1917, Montreal’s Harbour Commissioner stated the canal project “must be carried out and should be aggressively proceeded with”. That same year, the Panama Canal had opened and its construction difficulties had been almost monumental – difficult grades within relatively short distances, separate attempts by the French and Americans and thousands of workers’ deaths due to disease and accident. In comparison, the Great Lakes to Ocean route with 14 locks over 3,219km (2,000 miles) appeared a simple task.

Hydro-Electric Power Generation & Canada’s Growth

At this time, the potential of hydro-electric power generation was gaining the attention of politicians, investors and the public in Ontario, Quebec, throughout Canada and the United States. The development of hydro-electric power became a primary part of the Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company’s plans.

During the 1920s, Cantin aggressively promoted the power generation portion of the canal project, as it was becoming apparent lots of money could be made from the sale of power. He believed profits made from the power generation side of the project would help pay for the canal development.

The power-generation site Cantin proposed was between Lake St. Francis and Lake St. Louis, 40 km southwest of Montreal. This site is now that of Quebec Hydro’s generating station. The Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company needed to obtain the rights and properties at Beauharnois in order to fulfill the Company’s promotional promises of profit, power and canal development. Competing political and business interests in the Beauharnois site and the huge profit potential would clash in what became known as the Beauharnois Scandal of the 1930s.

The Beauharnois Scandal involved pay-offs to members of parliament and high-level officials by companies interested in developing the St. Lawrence River’s potential. The purpose of the pay-offs was to obtain the rights to develop the St. Lawrence River at Beauharnois from the Government to Canada.

Ultimately, Cantin was out-maneuvered by competing interests and arguably betrayed by Robert Oliver Sweezey, an engineer and member of Newman & Sweezey, a Montreal investment firm. Sweezey was contracted by The Great Lakes and Atlantic Canal and Power Company to represent their interests and to negotiate for the development rights of the Beauharnois location. Instead, Sweezey negotiated on his own behalf and a syndicate company he has formed to obtain the very same rights and licence he was hired to obtain for Cantin’s Company.